The biography of Lesueur by Ernest Hamy

Below we have reproduced Ritsert Rinsma's annotated translation of the introduction to Ernest Théodore Hamy's biography, The Travels of the Naturaliste Ch. Alex. Lesueur in North America (1815-1837), from Manuscripts and Works of Art in the Archives of the Museum of Natural History in Paris and the Museum of Natural History in Le Havre (1904). The complete work in French can be downloaded from the "Books" section of this website or by clicking on the link above. The following translation is different from the one by Milton Haber of 1956, completed and published by Hallock F. Raup in 1968 (Kent State University Press). The errors in Hamy’s text have been corrected using the books Alexandre Lesueur (2007) and Eyewitness to Utopia (2019) by Ritsert Rinsma, a historian and researcher at the University of Caen, France, who was able to compare the biography of Doctor Hamy with the manuscripts and original documents in the archives.

INTRODUCTION

[p. 1] All scientists know, at least by name, Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, the collaborator of François Péron during the famous Voyage to the Antipodes which provided so many important discoveries to the geographical and natural sciences in the first years of the last [19th] century. He was born in Le Havre on January 1, 1778, to Jean-Baptiste-Denis Lesueur and Charlotte-Geneviève Thieullent. Since his father was an officer in the Admiralty, he was accepted at the age of nine at the Royal Military School of Beaumont-en-Auge, and he remained there as a pupil from 1787 [p. 2] to 1796. [ERRATUM Jean-Baptiste Denis Lesueur was a civil servant, clerk, ship owner and merchant in Le Havre. Moreover, his son Charles-Alexandre never went to school in Beaumont-en-Auge. The establishment was in crisis in 1786 and was definitively closed in May 1789. See Rinsma, Lesueur, 23-27.] At the age of 18, he made his first campaign in the English Channel on board the sloop the Hardi and afterwards lived in Le Havre, waiting to find an employment where he could make use of his already remarkable talent as a draughtsman. [REMARK The career of C.-A. Lesueur in the Navy lasted only five weeks. He had enlisted to avoid military conscription. Disembarked by force by the local authorities on his return to Le Havre, he managed to get a dispension so that he would not have to go to the front. See Rinsma, Lesueur, 30-32.]

The armament of the two corvettes the Géographe and the Naturaliste which were to undertake, by order of the First Consul, the exploration of the Southern Lands still largely unknown, came to reveal to Lesueur his irresistible vocation for traveling and drawing. He no longer wanted anything else. Unable to get himself recruited as an artist, the positions being already taken, he embarked, as Jussieu said, under a vague title (a), happy to be able to announce to his father (who was not in favor of his departure) that Baudin, with whom he got along well, would employ him usefully, him and other comrades, without obliging him to do the work of a sailor.

"Our part will rather be to illustrate" he added, and, in fact, as soon as he arrived at Ile de France [Mauritius], on 4 Floréal Year IX [24 April 1801], he was in a position to announce that he was in charge "of drawing the objects of natural history, to go hunting and to help the secretary of the commander who has no shortage of work..." (b) Indeed, Baudin had appointed him to replace the landscape painter Milbert, whom he had to leave behind with Michel Garnier, genre painter, and Louis Lebrun, architectural painter, because all of them were more or less seriously ill. [REMARK Hamy misleads us by using the expression "more or less seriously ill." In fact the official draughtsmen did not want to continue their voyage of discovery with Captains Baudin and Hamelin. See Rinsma, Lesueur, 35.]

Of the ten naturalists of the expedition, four remained at Ile de France, and three others died of illness during the remainder of the journey. Péron and Lesueur alone survived, together with mineralogist Depuch and draughtsman [p. 3] Petit (c), fulfilling, from a natural history point of view, the purpose of the expedition. [ERRATUM Hamy suggests that Péron, Petit, Lesueur and Depuch were the only scientists to survive the journey and able to continue the scientific mission, which is not true.]

Péron was only sixteen months older than Lesueur (d); the two young men, who were brought together by common tastes and complementary aptitudes, formed a solid friendship, and it were their united efforts that ensured the unprecedented success of this historical voyage. [REMARK This is indeed what Georges Cuvier's report states. However, this report is incomplete and does not specify the contributions of the deceased scientists.]

The collections brought back by the Géographe and the Naturaliste consisted, according to Cuvier's testimony, of more than one hundred thousand specimen of animals. As for the new species, in the opinion of the Museum's professors, they exceeded 2,500. Péron and Lesueur had on their own discovered "more new animals than all the naturalists of this last age." [REMARK The expression "on their own" is of course greatly exaggerated.]

Cuvier's report on behalf of the Imperial Institute (e), from which these figures have been taken, convinced the Secretary of the Navy to publish an account of the voyage which would do so much honor to our country [France] (f). Péron, in charge of the historical part (August 4, 1806) quickly set to work and, in 1807, published the first volume which told the story of the expedition from the departure from Le Havre (October 19, 1800) until November 18, 1802. This volume was accompanied by an atlas comprising a plan and five pages of coastal views, twenty-two plates of drawings by Lesueur (representing landscapes, animals or [p. 4] ethnographic objects), and ten portraits of natives by Petit.

Péron had supervised the printing of his second volume up to the end of the XXXth chapter when the deterioration of a chest disease, of which he had contracted the germ during the voyage, forced him to go to Nice (g). He died in Cérilly (Allier), at the age of only 36, on December 14, 1810.

This death, "as distressing for the friends of the sciences," says Freycinet, "as it was for his family," interrupted the work "that had cost the author a great deal of trouble and which had been partly written on his death bed with a courage of which there are few examples”. When he died, Péron bequeathed his manuscripts "to his most intimate friend, to the faithful companion of his work and his research in natural history, to the good and modest M. Lesueur." (h) As he was "far from possessing," says Lesueur senior in one of the many petitions with which he assaulted the competent authorities… As he was "far from possessing the elocution and the warmth of his friend's engaging style, which had inspired his writings, his memoirs and his historical narrative, he did not hesitate to seek the benevolence and support of several distinguished men of letters to revise and correct the manuscripts that were to form the remainder of the second volume. Toulongeon, Latreille and Noël de la Morinière were thus successively requested to be associated with this publication. Toulongeon, who was part of this collaboration, [p. 5] died on December 26, 1812; Latreille and Noël declined, and the task of completing the second volume of the Relation du Voyage was devolved to Louis Desaulses de Freycinet, ensign, and later lieutenant of the expedition, who had just completed the publication of volume III devoted to hydrography. (i) [REMARK In fact, Lesueur was dismissed from his job during the Hundred Days for having chosen the side of the Royalists. Freycinet was appointed to replace him. After Waterloo and the fall of Bonaparte, Lesueur chose to depart with William Maclure. See Rinsma, Eyewitness, 27.]

This second volume was not to appear until 1816. The Empire had just fallen; everything that could recall its glories was systematically erased. The text of the last chapters was unscrupulously mutilated to avoid offending England, and a whole series of superb engravings by Lesueur and Petit, which were ready for printing, were suppressed for the sake of economy.

Lesueur did not know about this painful sacrifice until later. He had left Paris for America on the fifteenth of the preceding August. The fall of the Empire had particularly affected the unfortunate artist. He had not been able to get paid by the Droits-Réunis [state royalties] for many drawings executed after 1812 in the offices of the first division. A factory which employed him had to close its doors at the beginning of 1814; he had only a modest pension of 1,500 francs given to him by the Emperor on August 24, 1806 (j), and a small apartment at the Sorbonne which he shared with his father. [ERRATUM Lesueur's pension was 3,000 francs a year, not 1,500 francs. The fact of having supported the Royalists enabled him to keep this pension throughout his life. Hamy is therefore mistaken about Lesueur's “very embarrassing situation”. See Rinsma, Eyewitness, 26.]

It was in this very embarrassing situation that one day Lesueur found [p. 6] on his road the rich and learned American geologist and philanthropist, William Maclure (k), who easily managed to persuade him to accompany him to the New World. (l) [REMARK Lesueur met Maclure in Paris for the first time in 1804, shortly after his return from the Baudin expedition. See Rinsma, Eyewitness, 27.]

After having been involved in commercial activities in New York and London for more than twenty years, William Maclure came to France for the first time in 1803, charged with an official mission, together with Mercer and Burnett [SIC Barnet], to present the claims of American citizens who had suffered damages in the course of the Revolution. After completing this delicate task and preparing the treaty signed on 10 Floréal Year XI (April 30, 1803) (m), he made several geological trips in Europe, to train himself to achieve, what he called, the great object of his ambition, a first geological survey of the United States. [REMARK Maclure's geological trips and travels had started long before 1803. See Rinsma, Eyewitness, 82.]

Reduced to his own strength, without official support and without a collaborator, Maclure was however in a position, less than six years later, to submit to the American Philosophical Society (n) [p. 7] a whole series of precise observations, coordinated with method, and covering in their entirety the territories of the Union from the Saint Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico (o). Maclure returned to Paris after the Hundred Days to look for a travelling naturalist who could accompany him in the complementary survey which he was contemplating. Lesueur was introduced to him, and he had no difficulty convincing the adventurous artist to follow him to the United States. [REMARK As noted above, Lesueur met Maclure in Paris in 1804, shortly after his return from the Baudin expedition. See Rinsma, Eyewitness, 27.]

On August 8, 1815, William Maclure and Alexandre Lesueur signed a contract containing nine clauses which would govern their relations during the planned voyage. (p) Lesueur agreed to make all the drawings that concerned natural history, to unite all the notes on the habits and manners of the animals observed, and to preserve in alcohol or to have stuffed those specimens which Maclure deemed worthy of being part of a collection.

Once the trip behind them, the artist had to contribute by supervising the work of engraving ordered by the head of the expedition. If a publication were to follow, it would be "under the names of both MM. Maclure and Lesueur" and the profits and benefits that might result from it would be "put at the disposal of Sieur Lesueur, after deduction made of all the expenses of the enterprise." In case no publication should follow, Lesueur had the possibility to constitute an identical collection for himself out of the gathered specimens.

All the general expenses of the trip having been taken care of (cost of passage, transport of belongings, food, accommodation, [p. 8] etc.), as well as some special expenses (supplies of paper, pencils, colors, jars, alcohol, etc.), Lesueur was to receive a salary of 2,500 francs, payable quarterly. The intended duration of the trip would be two years. In case of an accident involving M. Lesueur during this period of time, Maclure agreed to return all the personal belongings that Lesueur had taken with him to his family, everyone "depending in this matter on the benevolence and trust that Mr. Lesueur was placing in him." A final clause assured the traveling artist of his return to France together with the things that belonged to him, but "without insurance for the risk at sea". [NOTE This contract is reproduced in Rinsma, Lesueur, 342-344, as well as in Eyewitness, 5-6.]

The two naturalists left Paris (q) on August 15 (r). They arrived in Dieppe on the 17th and disembarked in New Haven [England] on the 18th (s). Lesueur was very happy to resume the active career of traveling naturalist, which had provided him with the best moments of his life. The first evening found him observing and drawing, among the limestone rocks that cover the beach of New Haven, the honeycombed Sabella of Ellis (t). While he was studying the shapes and habits of the annelids, bryozoans and gorgonians, Maclure took the cross-section of the cliffs between New Haven and Brighton.

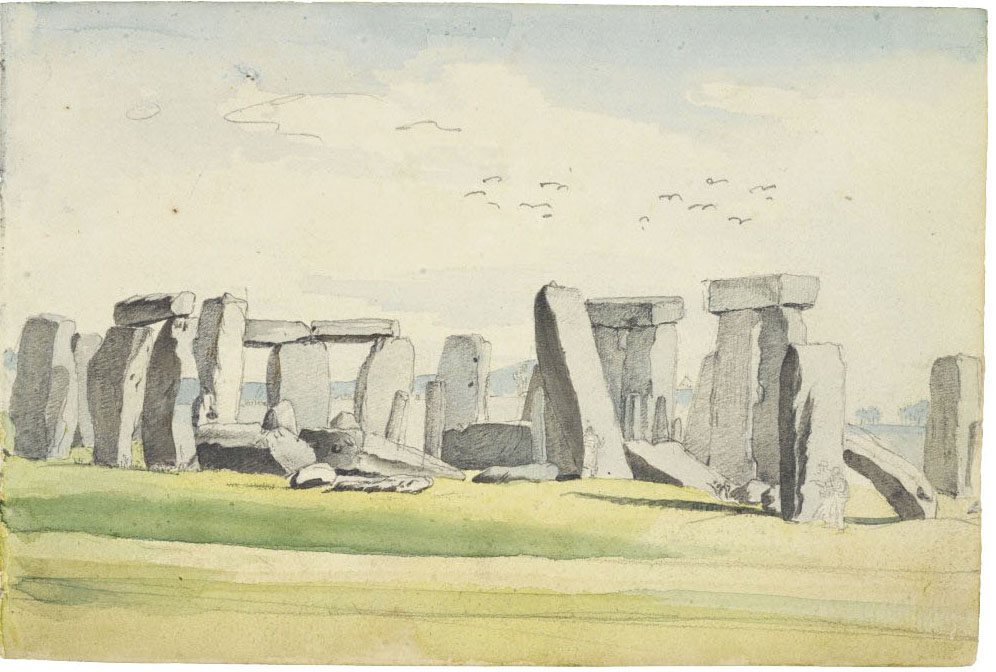

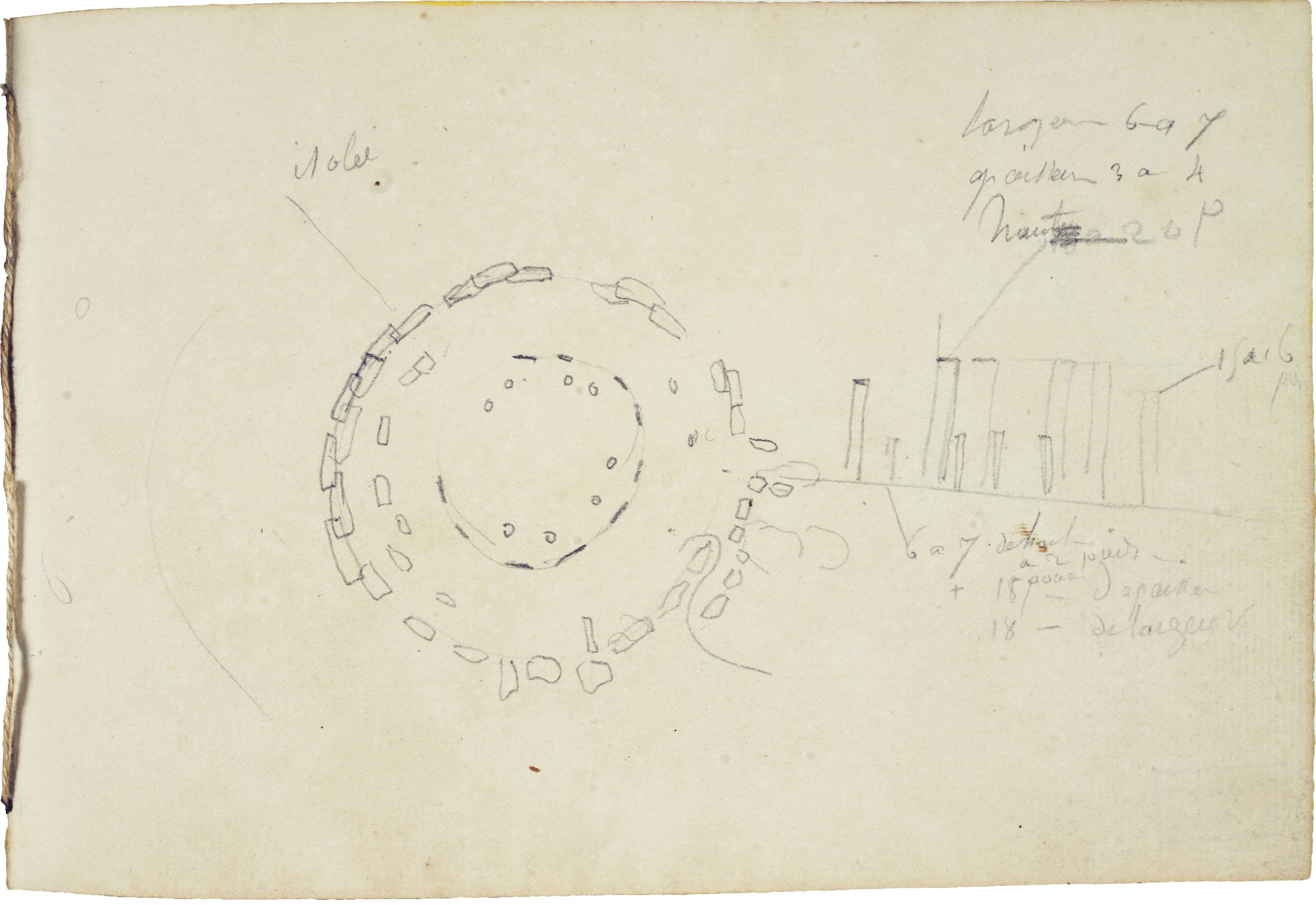

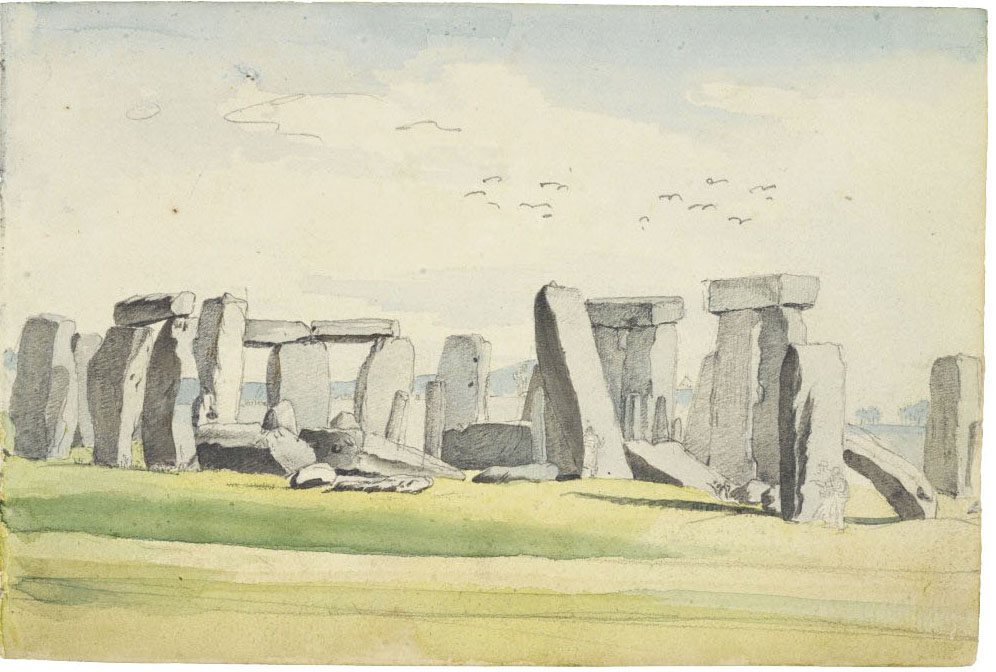

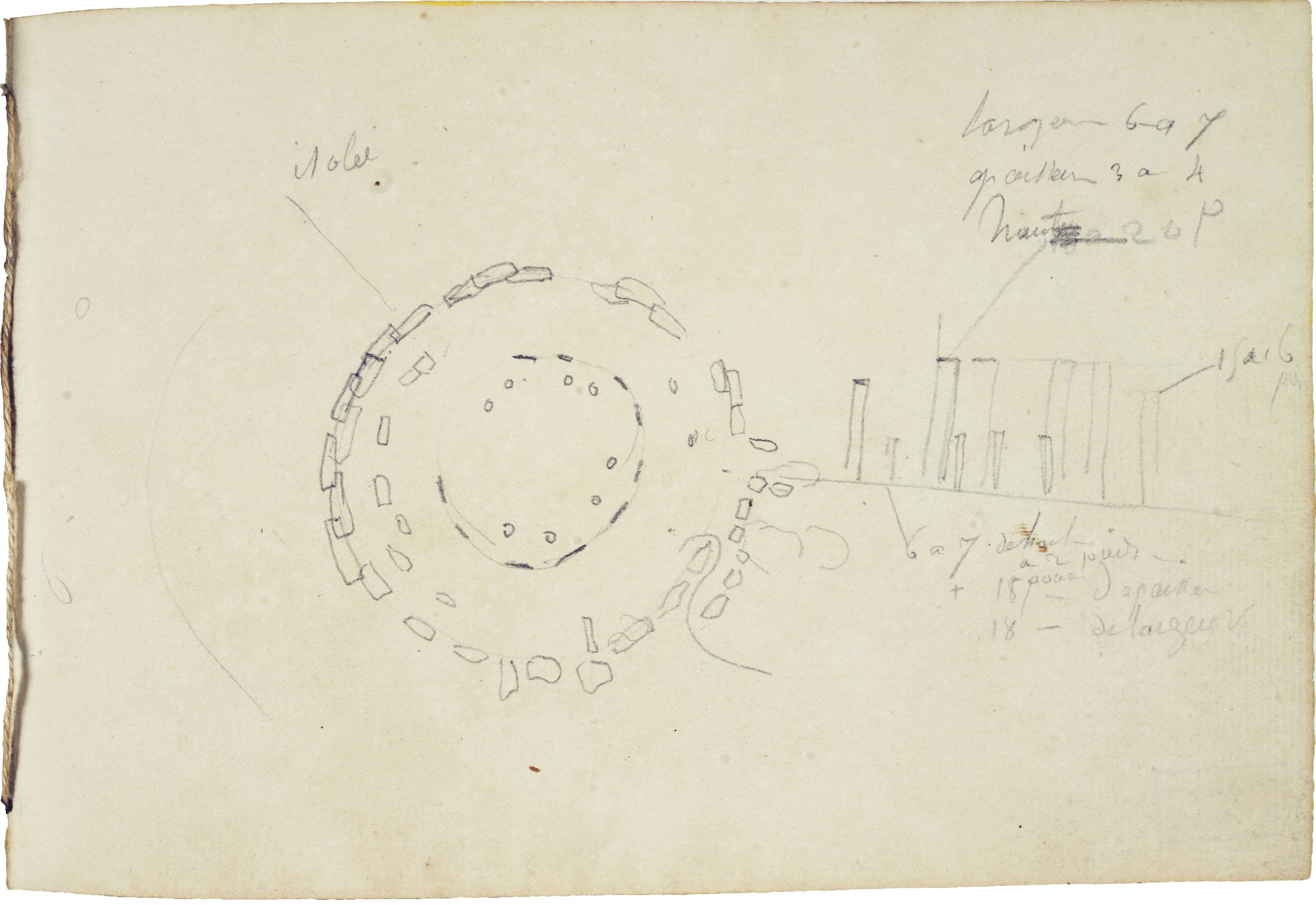

[p. 9] Then they departed for London, and a note by Lesueur gives his impressions of the Hunter Museum (u), Kew Gardens (v), the drawings of Bauer, the birds of Bulow, and the fossils of Sowerby. For Cuvier he sketches several rare samples belonging to this last naturalist [Sowerby], which he sent to him via Leach who was going to France. On October 4, after a four-day journey during which they visited the famous megaliths of Stonehenge (of which Lesueur left a valuable watercolor) (w), they returned to Falmouth where the packet boat Louisia was being fitted out for the Antilles.

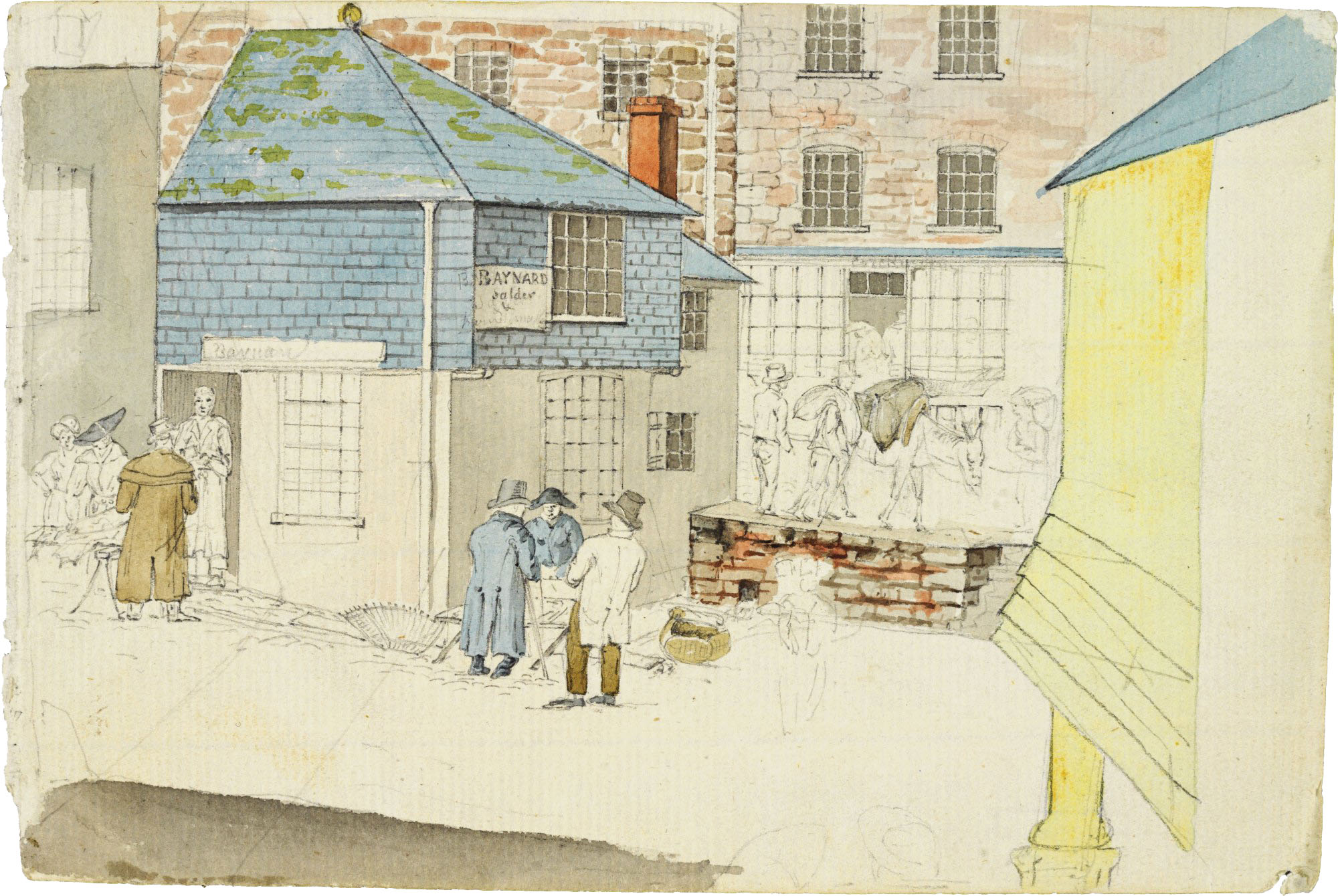

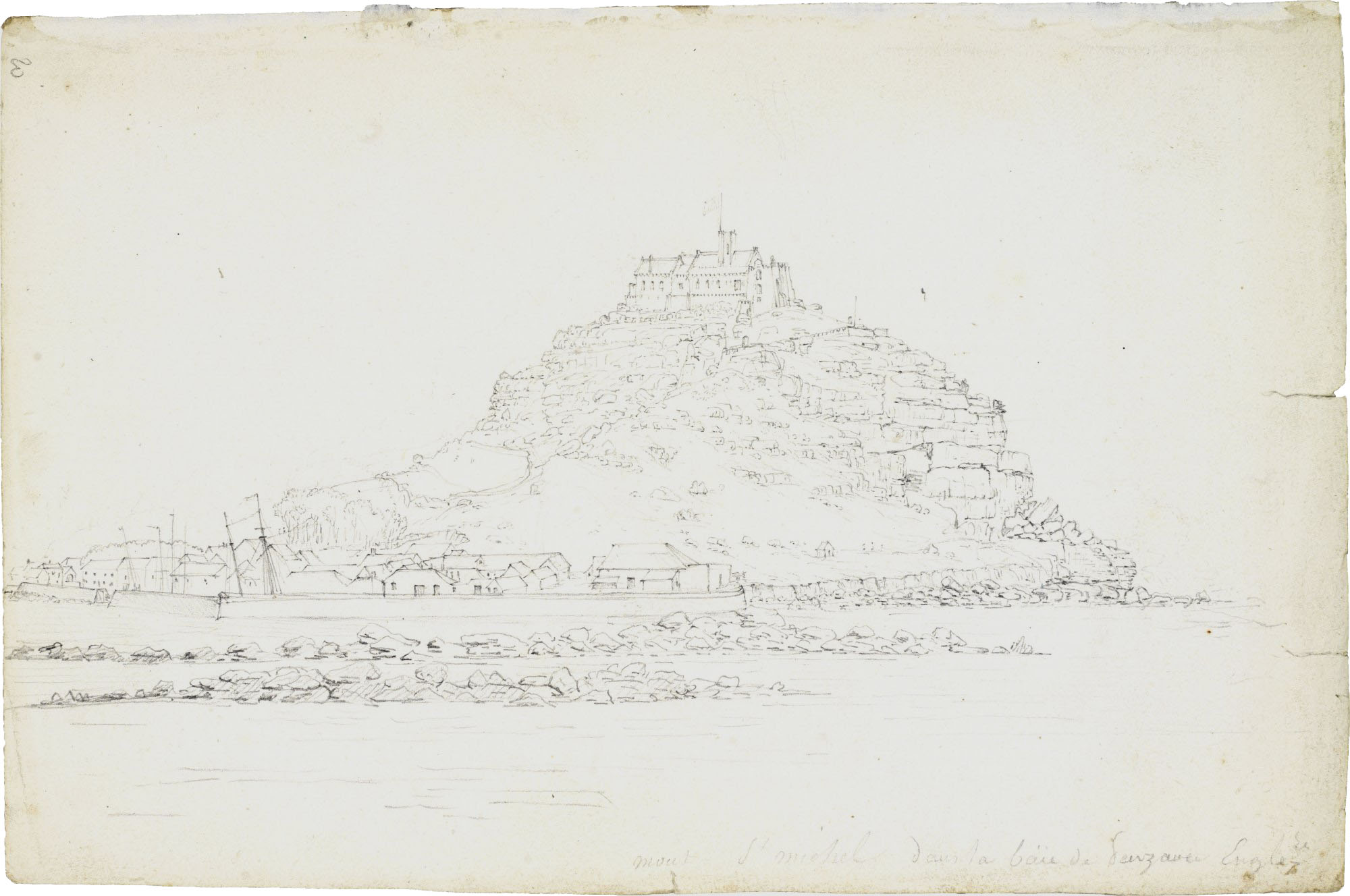

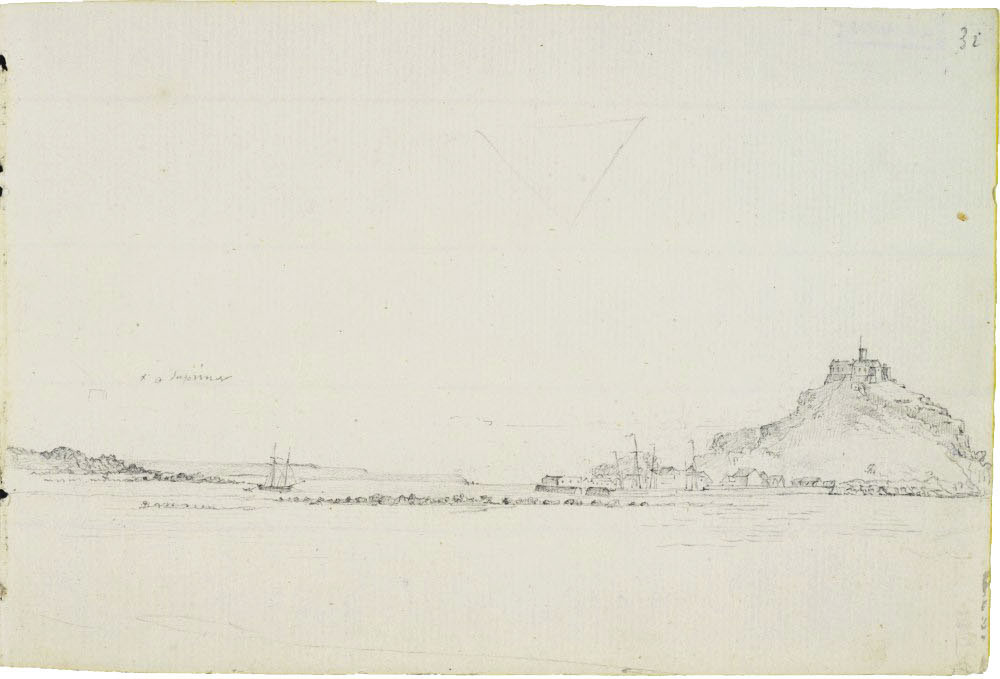

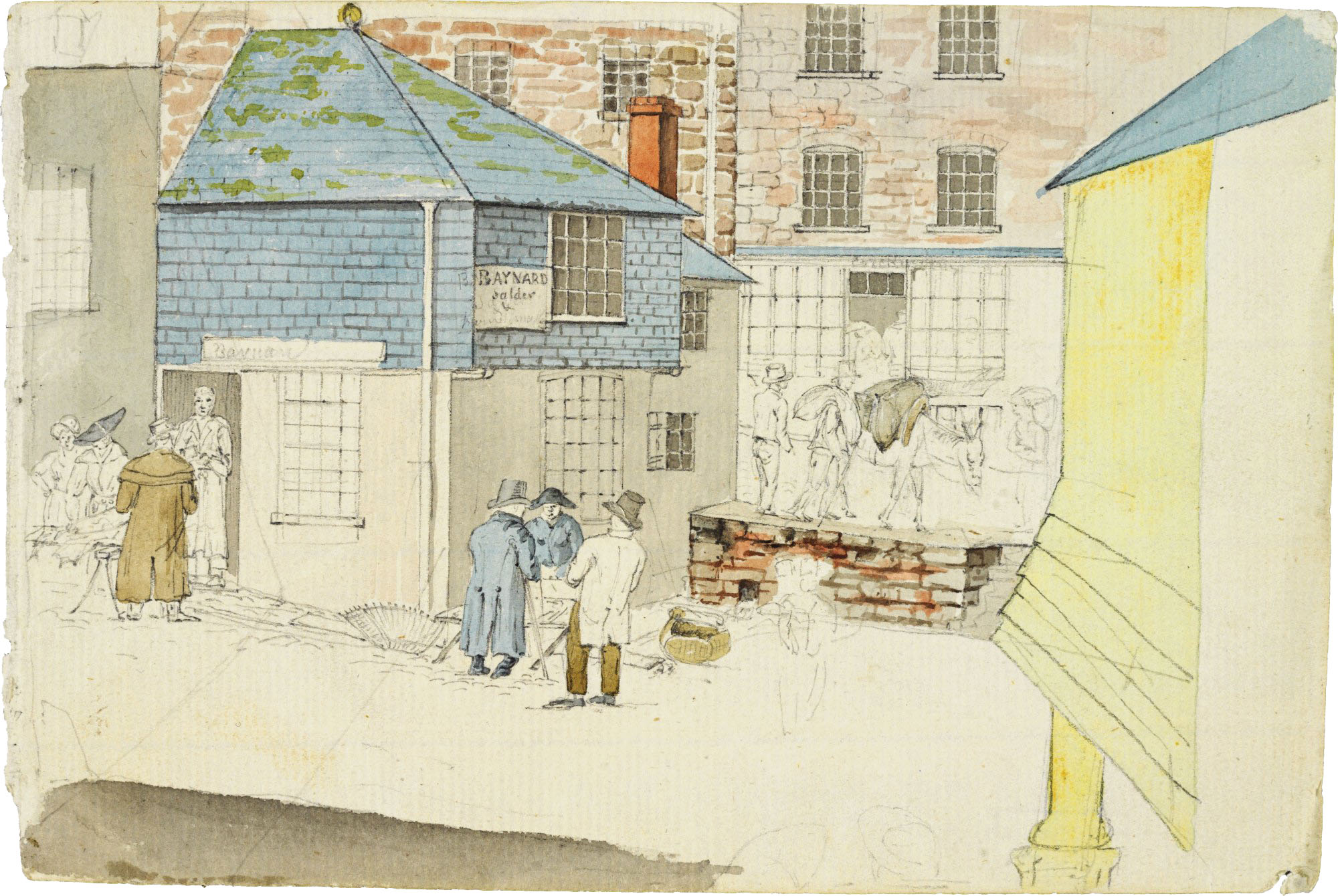

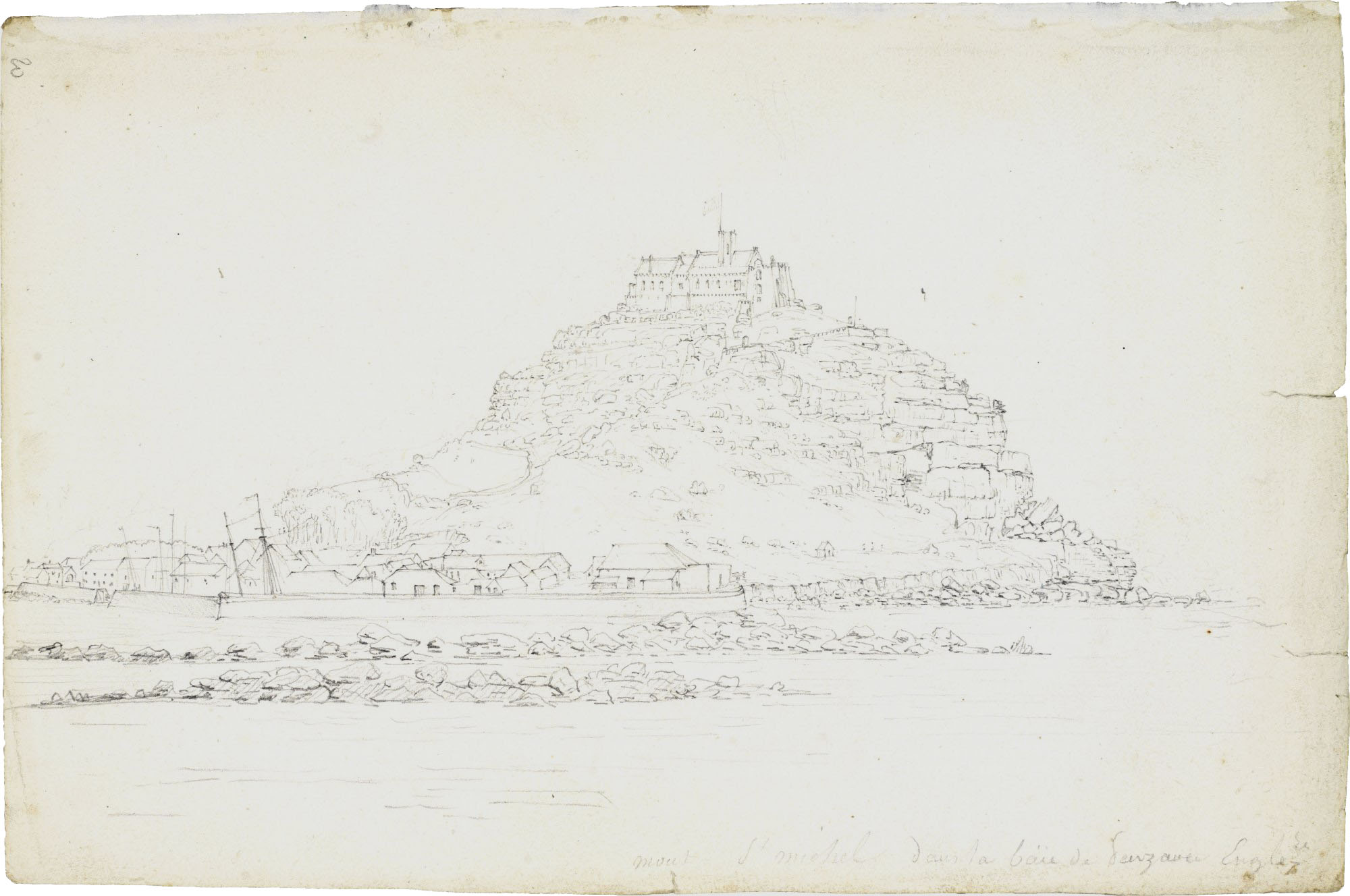

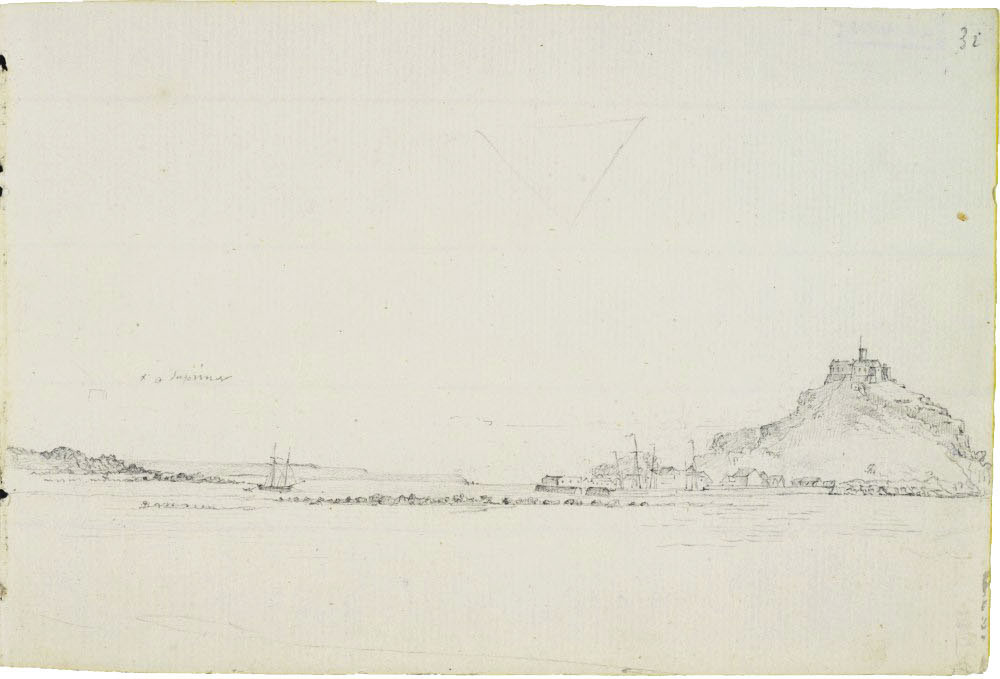

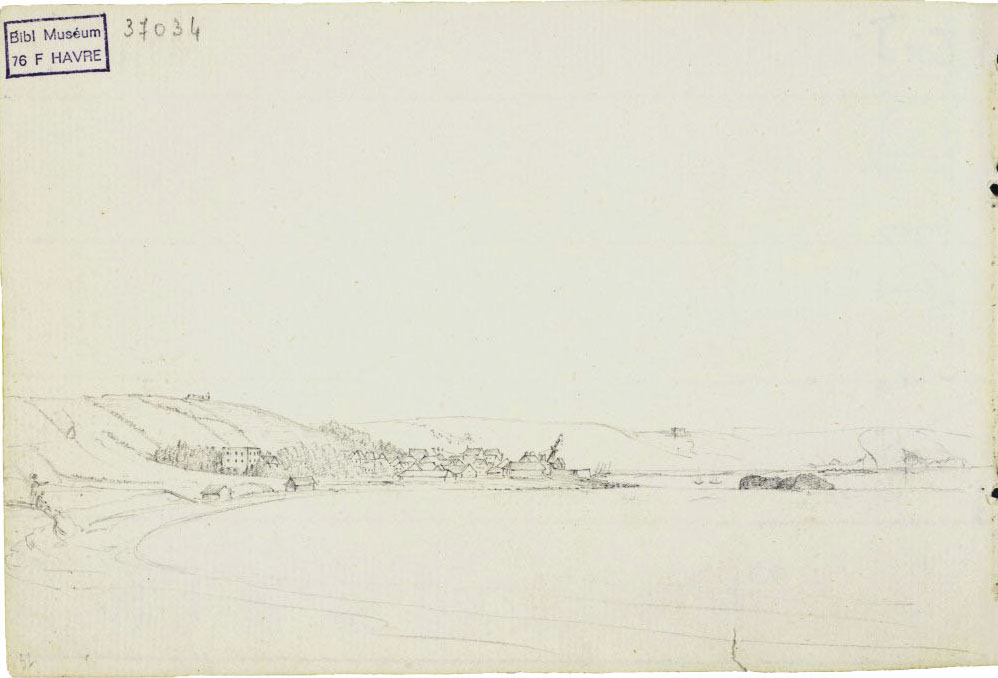

Waiting for the day of departure, the travelers roamed the neighboring country; Penzance, the home of Humphry Davy, where Lesueur drew the humble little house made famous by the first experiments of this great chemist (x); Saint Michael's-Mount, which picturesque physiognomy he also reproduced; Land's End and its bare granite rocks; the Moving Rock; Longship's Stone and its famous lighthouse, [p. 10] which dated from 1797 and of which Lesueur made a landscape drawing in sepia; Saint-Just and its wild rocks; Saint-Yves and its steep gorge; and finally Cooper House and Redruth in the center of the peninsula. A geologist from this small town, Doctor Paris, introduced Maclure to this mining district. Lesueur eagerly sketched the main sites, or he studied the marine animals so abundant along these shores; kingfishers, bell animalcules, planarians, sea-nymphs, etc. In one place he observed a small species of ascidiacea, living in colonies around the stems of a rockweed; in another he saw a flatworm, moving slowly in the middle of long bundles of lines which serve as nets for this hairy fisherman.

The Louisia was not ready yet and a last trip took Maclure and Lesueur to the Lizard Cape via Helfort and Saint-Yvan. Here they admired the rocky pyramid known as The Giant, the arches and the sea caves, Saint-Kynan, etc.

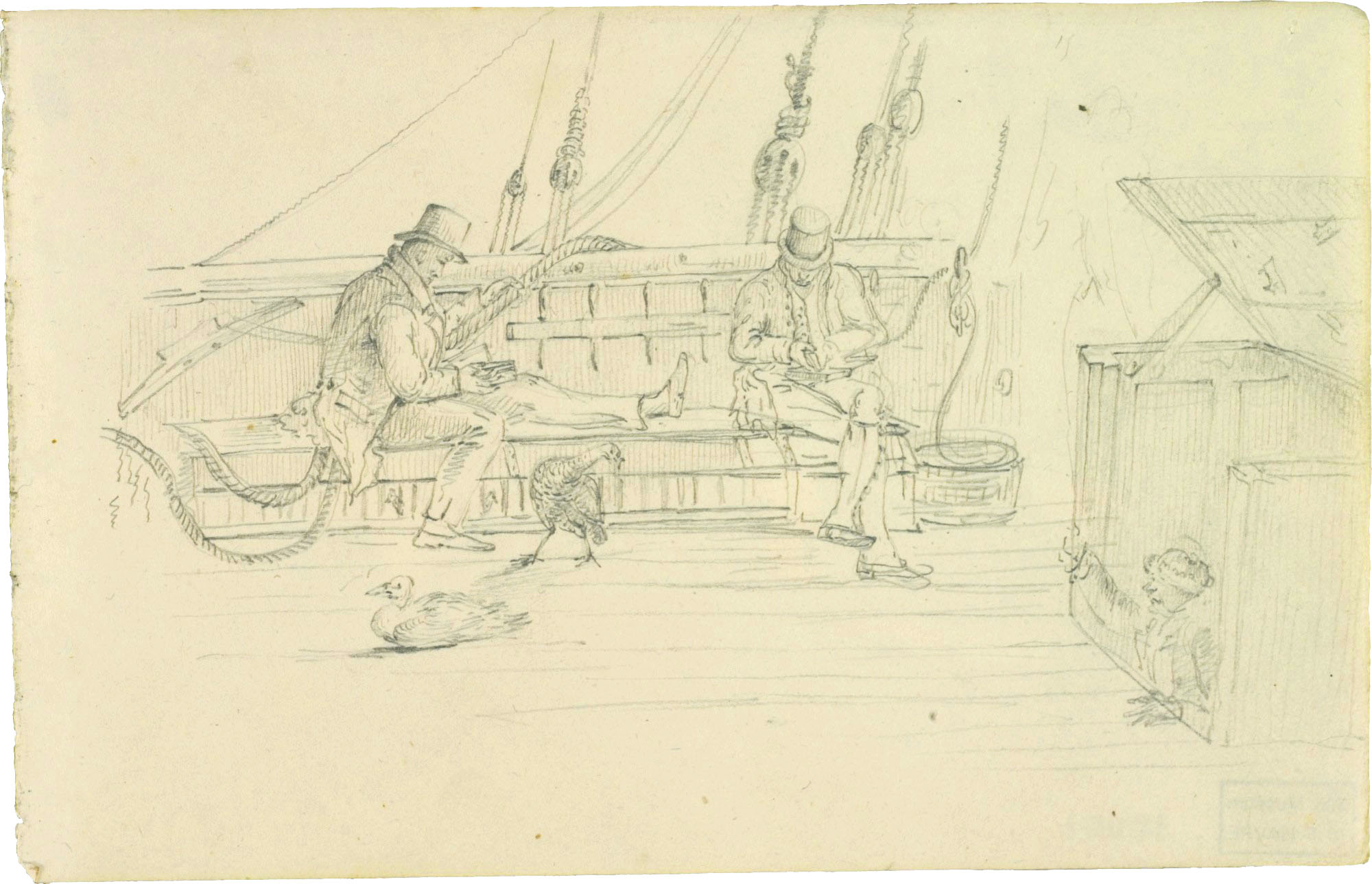

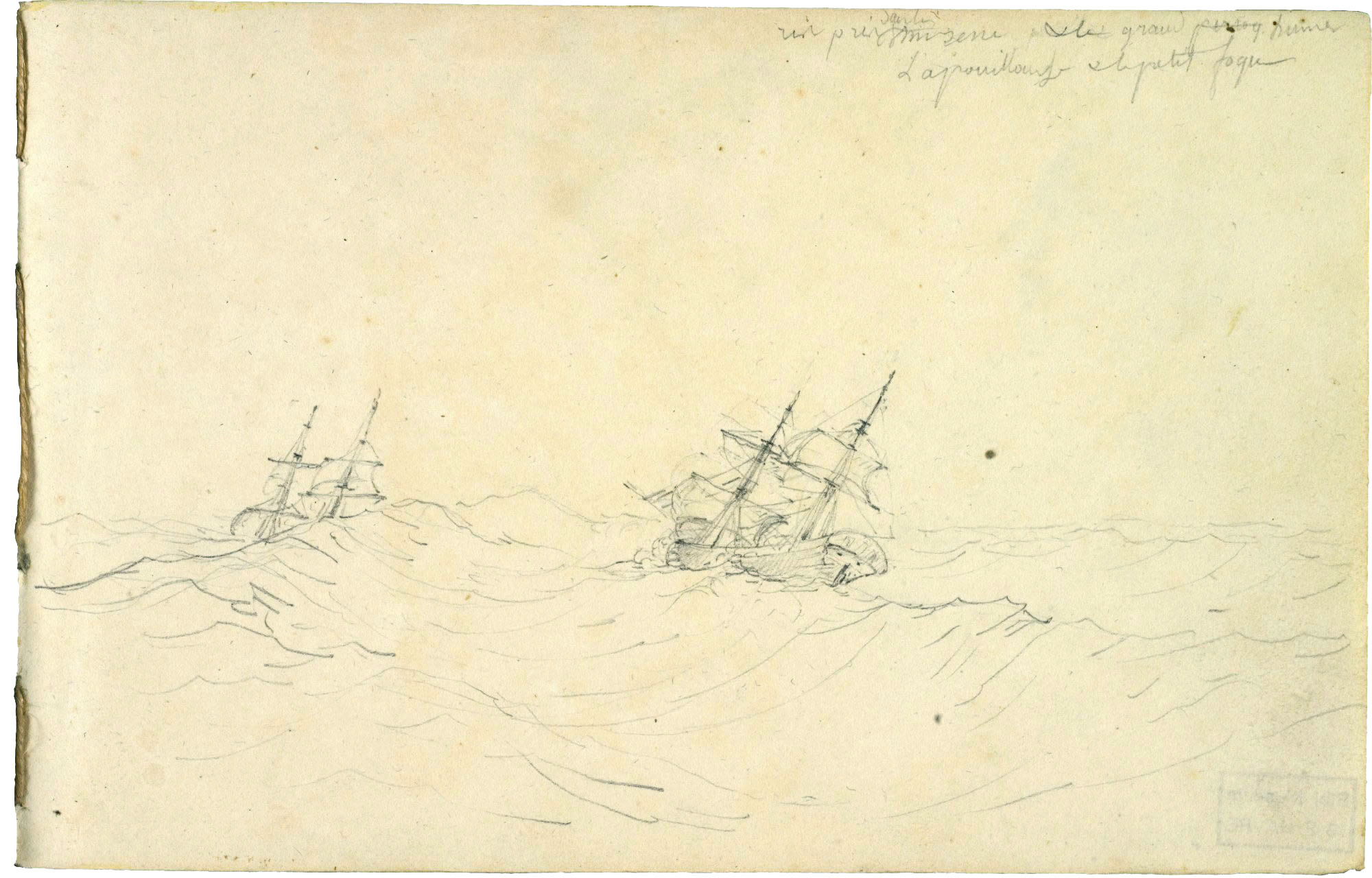

Finally, on November 16, after a delay of 43 days, the Louisia, Captain Gibbon, fourteen crewmembers and some English passengers left Falmouth for Barbados (y), and, with the same zeal as on board the Géographe not so long ago, Lesueur resumed writing down the little facts of every day, the ones that could be of interest to the natural sciences. As for the phosphorescence of the ocean, of which he understood the multiple causes, he marked its intensity every night, taking the temperature of the sea at the surface, and next comparing it to that of the open air or the interior of the vessel. The animals he came across: dolphins, petrels, phaetons, flying-fish, dorados, etc.

[p. 11] Net in hand, as soon as the weather permitted, he would try to catch, as it floated by, some unknown creature that had lost itself on the top of a wave; such as this shell-fish, for example, similar to a shrimp, and whose body lights up brightly; or that little geryonia with ringed tentacles and very vivid movements; a mollusk related to the carinarians, which he seized as it was swimming along; a new specimen of physalia, etc.; next came some physophoridae, velellas, hyales and atlantes. Once they caught a dolphinfish of which he reproduced the beautiful colors and analyzed the [contents of its] stomach.

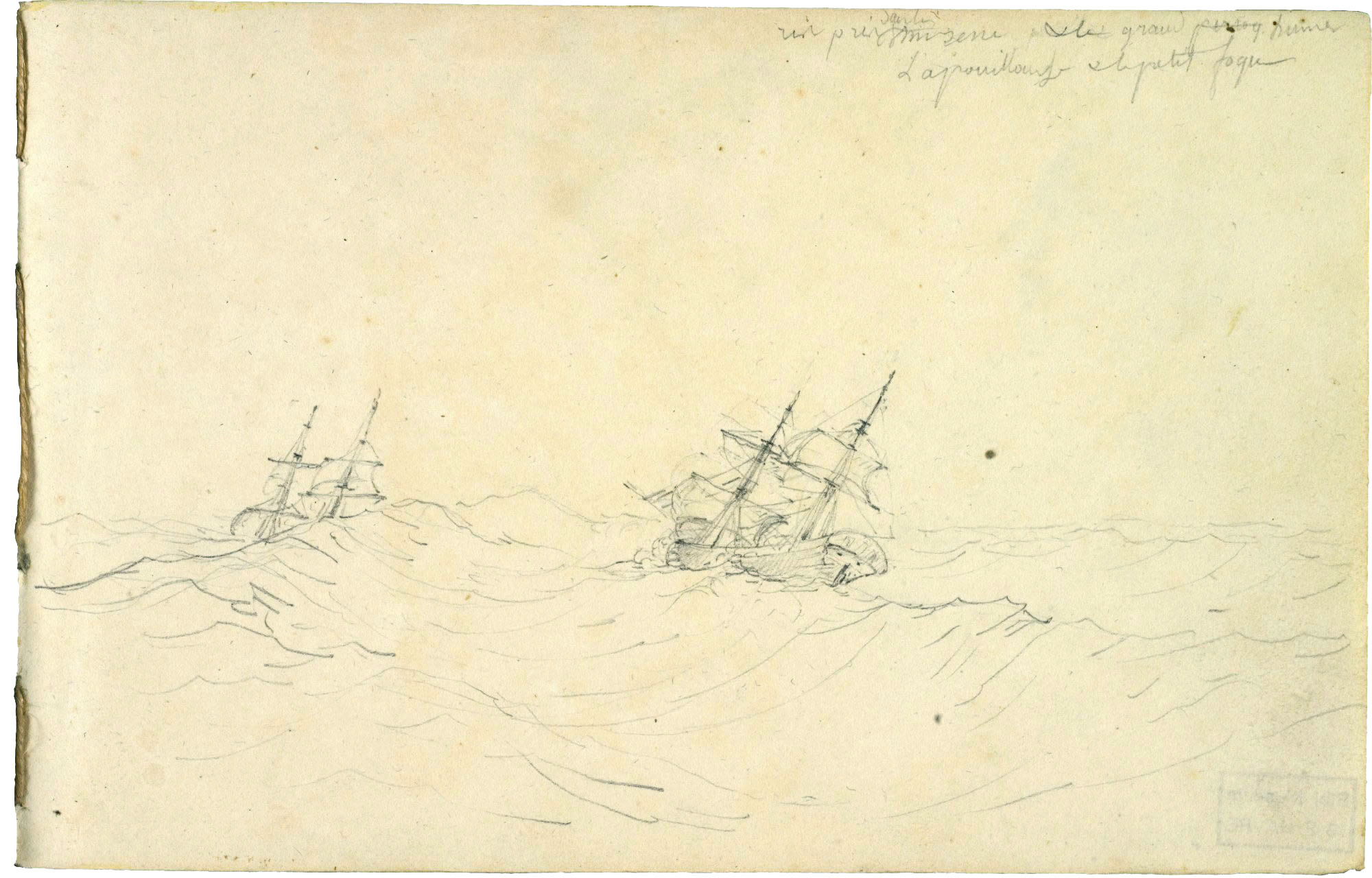

The weather grew stormy. December 5, the ship fell victim to the most violent assaults; the main yard was broken, the foremast was taken away by the sea, and Lesueur, who compared this hurricane to the ones that caused damage to the Géographe near the Cape of Good Hope and Bass Strait, assures us that he never experienced anything like this during the entirety of his great journey. The calm returned. The sea was beautiful. He picked up his net again and showed his companion the fragments of that same spirula which, when it was discovered during the Voyage to the Southern Lands, shed so much light on the history of the ammonites.

This encounter, and the circumstances in which it had just occurred, recalled the memory of a dearly cherished collaborator, and Lesueur, whose unskilled pen always betrayed his sentiments, wrote in an embarrassed style on one of the pages of his notebook an emotional and forceless appeal to the one who, a few years earlier, knew so well how to give a brilliant description of their common observations.

a. He first appears in the registers of the Geographe as a novice helmsman. [ERRATUM In Nicolas Baudin’s logbook Lesueur is first listed as assistant gunner.]

b. Arch. Mus. of Havre.

c. The love for adventure led this young artist to enlist in the expedition just like Lesueur, where he started as an assistant gunner (Cf. E. T. Hamy, L'oeuvre ethnographique de Nicolas-Martin Petit (L'Anthropologie, Sept.-Oct. 1891).

d. He was born in Cérilly (Allier), on August 22, 1775.

e. This report is printed at the beginning of volume one of the account of the expedition (p. i-xv).

f. Ibid., p. xv.

g. "The health of my friend Péron not having improved," Lesueur wrote to his father on January 18, 1809, "he was advised to make a little trip to Nice where I intend to accompany him. Our departure is set for Saturday the 21st of January" (Arch. Mus. Havre).

h. Voy. de découv. aux Terres Australes. Historique, t. II. Preface by M. Louis de Freycinet. Paris, Impr. Roy. 1816, in-4°.

i. Lesueur did not follow his father in the quarrelsome demands he addressed to Freycinet about this appointment, which did not take into account the imperial decree of August 4, 1806. He was mainly preoccupied with combining into one volume the natural history memoirs he had produced together with Péron, who had wanted these to be dedicated to the Countess of Mollien. There are two versions of this dedication in the archives of the Museum of Le Havre, one of them bears the date of June 6, 1815. Lesueur's departure for America interrupted this intended publication.

j. See the text of Champagny's letter, August 1806, announcing the imperial decision to Lesueur in the notice by Dr. Ad. Lecadre, Dicquemare et Lesueur, Le Havre, 1874, in-8°, p. 12.

k. II était fils de David et d'Anna Maclure et était né en 1763 à Ayr, en Ecosse (A Memoir of William Maclure, Esq. Late President of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, by Samuel George Morton, M. D. one of the Vice-Presidents of the Institution. Read July, 1, 1841. Philadelphia, 1841, in-4°, 37 pp. avec portrait).

l. These are the words in which Lesueur recounts his enlistment. "Beseeched for a long time by Mr. Maclure to accompany him on the excursions he wanted to take in the United States, I allowed myself to be tempted, so much I still wanted to visit some distant seas in order to add a few more facts to my numerous observations..." [REMARK Hamy has reformulated Lesueur’s sentences. For the exact wording, see Rinsma, Lesueur, 63-64]. Moreover, Lesueur recognizes that the offer was generous and he appreciates the advantage of having an educated traveling companion. (See at the Museum of Le Havre the small 10-page notebook entitled: "Crossing from Falmouth to the United States of America, sketches and views since our departure").

m. This treaty, dated April 30, 1803 (30 Floréal Year XI) was signed by Bonaparte, First Consul, and Barbé-Marbois, for France, and for the United States by Robert Livingston, Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States, and James Monroe, also a member plenipotentiary and envoy extraordinary to the government of the French Republic.

n. This memoir is entitled Observations on the Geology of the United States explanatory of a Geological Map. It was read on January 20, 1809, and published in the sixth volume of the Transactions of the Society. Laméthrie, a friend of Maclure, provided a French summary, written by the author himself, who knew our language very well (Journal de Physique, t. LXIX, p. 201-215, 1809).

o. In this extraordinary undertaking, writes Morton, we have the forcible example of what individual effort can accomplish, unsustained by Government patronage, and unassisted by collateral aids, p. 10.

p. Articles of conditions and commitments made and concluded on this 8th day of the month of August 1815, etc. (Arch. Mus. Havre, ms.)

q. Lesueur took 473 kilograms of paperback and bound books with him, as well as office supplies valued at 200 francs, natural history objects estimated at 500 francs, and clothes and linen worth 1,500 francs (Arch. Mus. Havre).

r. Lesueur wrote on the 9th to the Assembly of Professors of the Museum to offer them the plates of the first two deliveries of his Jellyfish and to announce his departure for London, and he asked "a word of recommendation for some members of the most recommendable societies of this capital" (Arch. Nat. Hist. Mus. of Paris, box 33).

s. I borrow these precise details from an unfinished note in Lesueur's hand, entitled Itinerary of the Voyage of Ch.-A. Lesueur since August 15, 1815 until his return to France on ... 18…, and to his travel diaries which are part of a batch of papers that were given to me by one of his nephews, the late Mr. Quesney. [REMARK The diaries given to Ernest Hamy by Edouard-François Quesney remained in his personal possession and were lost after Hamy’s death in 1809.]

t. It is by the description of this curious animal that he inaugurates the notebook entitled: Zoological and geological descriptions, begun August 18, 1815, in New Haven, England. - The first forty-seven pages contain notes on several living mollusks, Sabella, Flustra [foliacea], and fossils, Cerithium, etc., observed at New-Haven, Falmouth, etc., the remainder (10 pages) is a travel journal of the trip from Penzance to Saint-Yves, etc. [REMARK This travel journal was also lost after Hamy’s death in 1908.]

u. "Mr. Hunter's museum," Lesueur writes, "contains a collection of objects all the more interesting because each of them were prepared by the doctor himself" (the docter the museum was named after). There are in particular "many jars containing a multitude of very well prepared anatomical parts taken from all the kingdoms of nature, arranged part by part, in such a way that any portion of the [exhibited] animals show all the [anatomical] organizational differences, following each series from the plant to the man."

v. The greenhouses are very rich in foreign plants. The director showed us one after the other. They contain many interesting plants that we do not have in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. The collection of those of New Holland is quite complete. All the species of Banksia which we don't have are gathered there." (Ibid.)

w. This watercolor, which shows the state of the famous monument in 1815, is found with a few others (as well as a number of charming drawings) in a small oblong portfolio, entitled Stay in England in August 1815, which is kept in the library of the Museum of Le Havre.

x. It is a small house composed of a ground floor and a low second floor, in which, under the edge of the roof, is a window of 16 small panes - the window of Humphry Davy. Lesueur drew this humble home twice; a view of the street and the house alone. These would be images to reproduce.

y. A second small portfolio contains 88 pages of notes relating to this crossing; ten of these pages contain meteorological observations taken during 33 days from Nov. 24 to Dec. 24, 1815. [REMARK Part of this portfolio still exists and is catalogued under number 37 047 of the Lesueur Collection in the Le Havre Natural History Museum.] An oblong notebook n° 2 is entitled Zoological description of the animals observed during the crossing from Europe to the West Indies on the liner the Louisia Captain Gibbon. [REMARK This notebook by Lesueur appears to be lost like so many others. See notes (s) and (t).]

|

|

Scree at Cap de la Hève, by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (c.1840) - Lesueur Collection 32 054, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

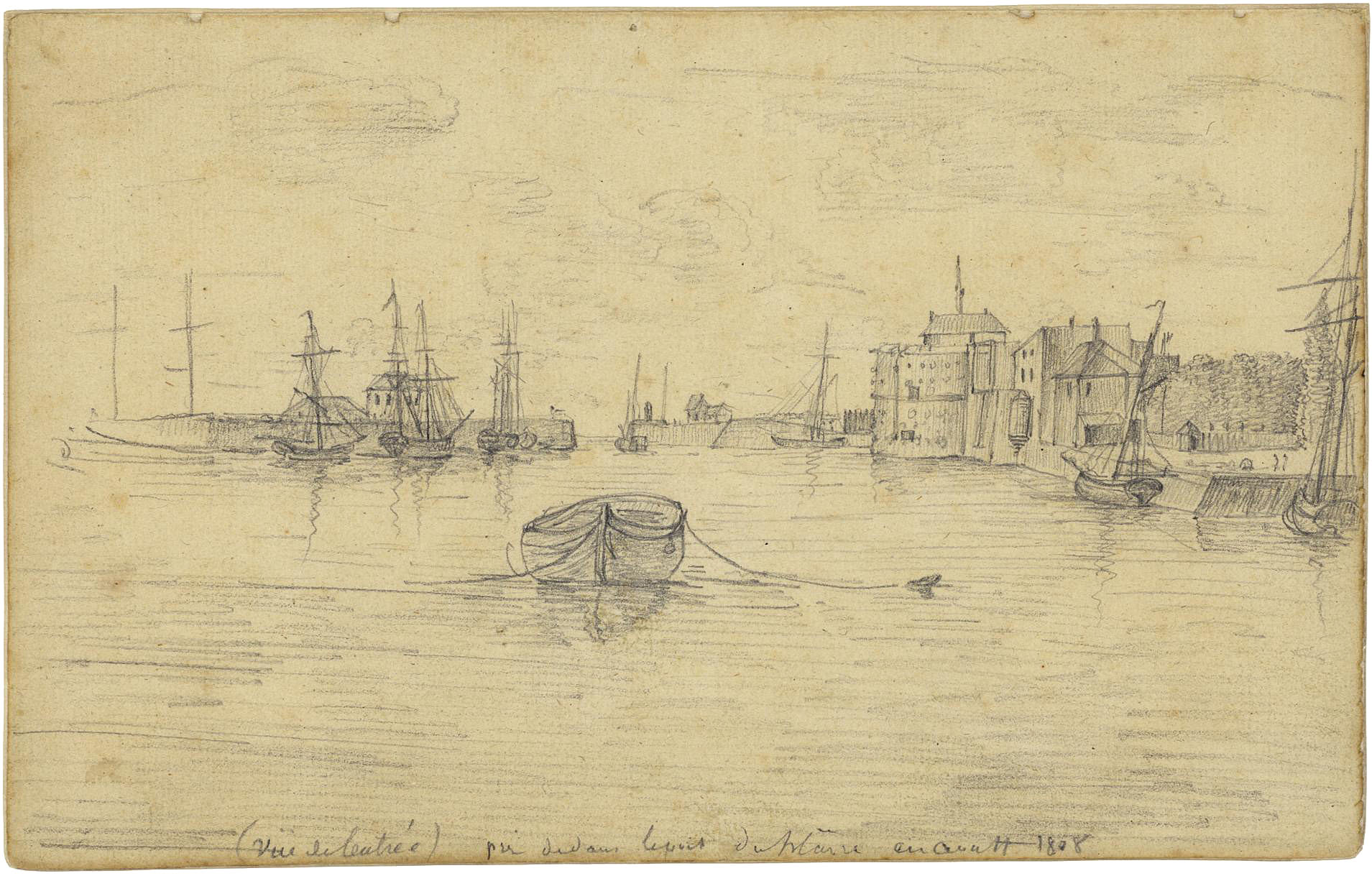

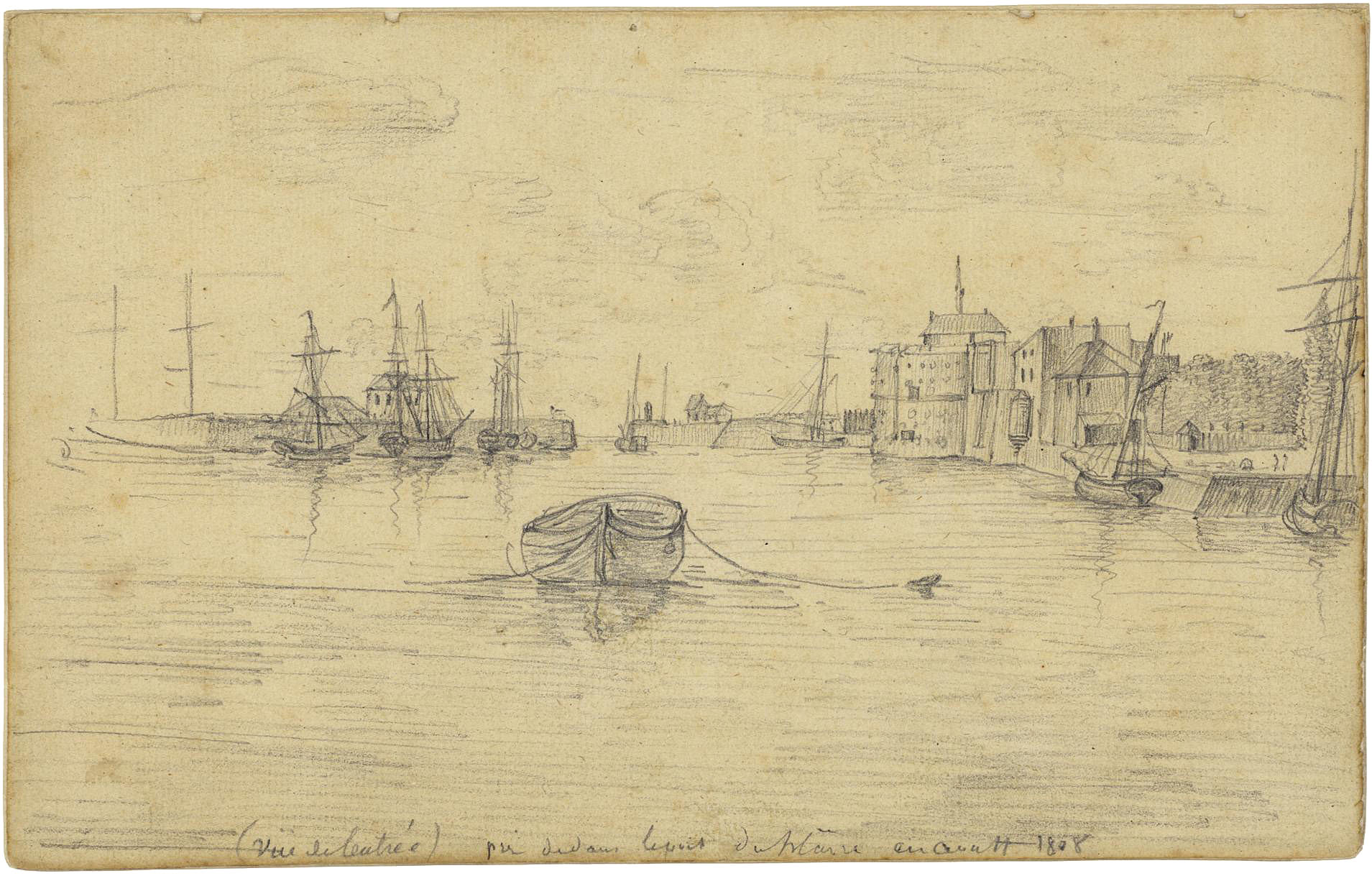

Entrance to the port of Le Havre, by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1808) - Lesueur Collection 36 026, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Scree and entrance to the port of New Haven, by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 002R, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Greenwich Observatory (London), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 010R, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Megalithic site of Stonehenge (Wiltshire), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 011V, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Megalithic site of Stonehenge (Wiltshire), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 012R, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Plan of the megalithic site of Stonehenge (Wiltshire), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 014R, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Cobalt mine near Redruth (Cornwall), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 021R, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Birthplace of Sir Humphrey Davy (Penzance), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 031R, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Wreck of the Delhi in Mount's Bay (Marizon), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 032R, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Eddystone Lighthouse at Land's End (Cornwall), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 038R, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Saint Michael's Mount (Cornwall), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 048, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Saint Michael's Mount in Mount's Bay (Cornwall), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 035R, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

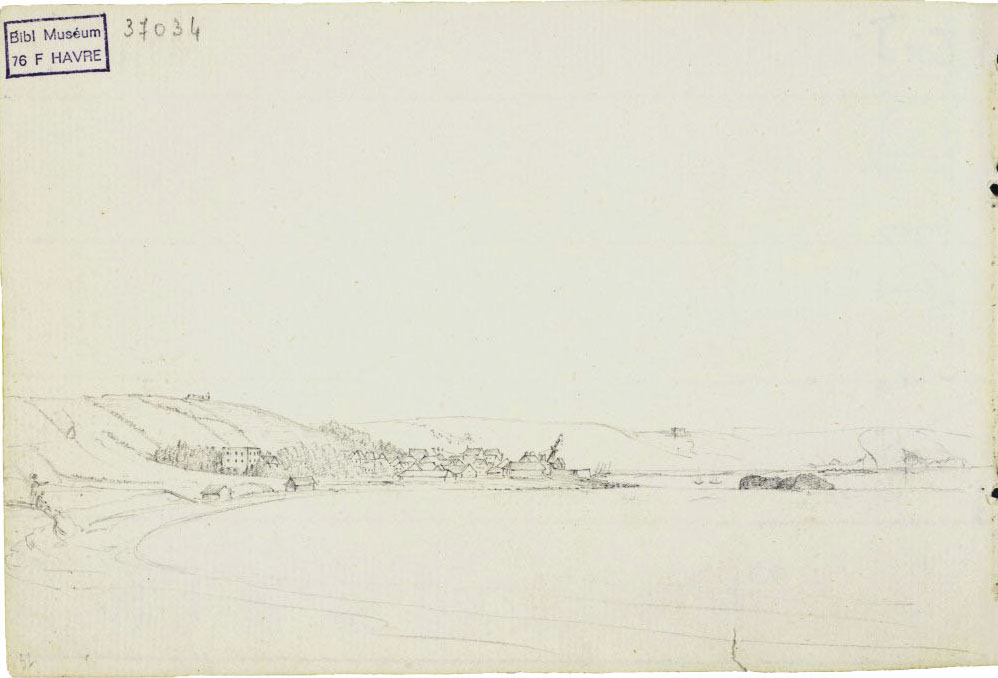

Penzance and Mount's Bay (Cornwall), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 37 034V, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

Crossing the Atlantic Ocean, by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 38 001R, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

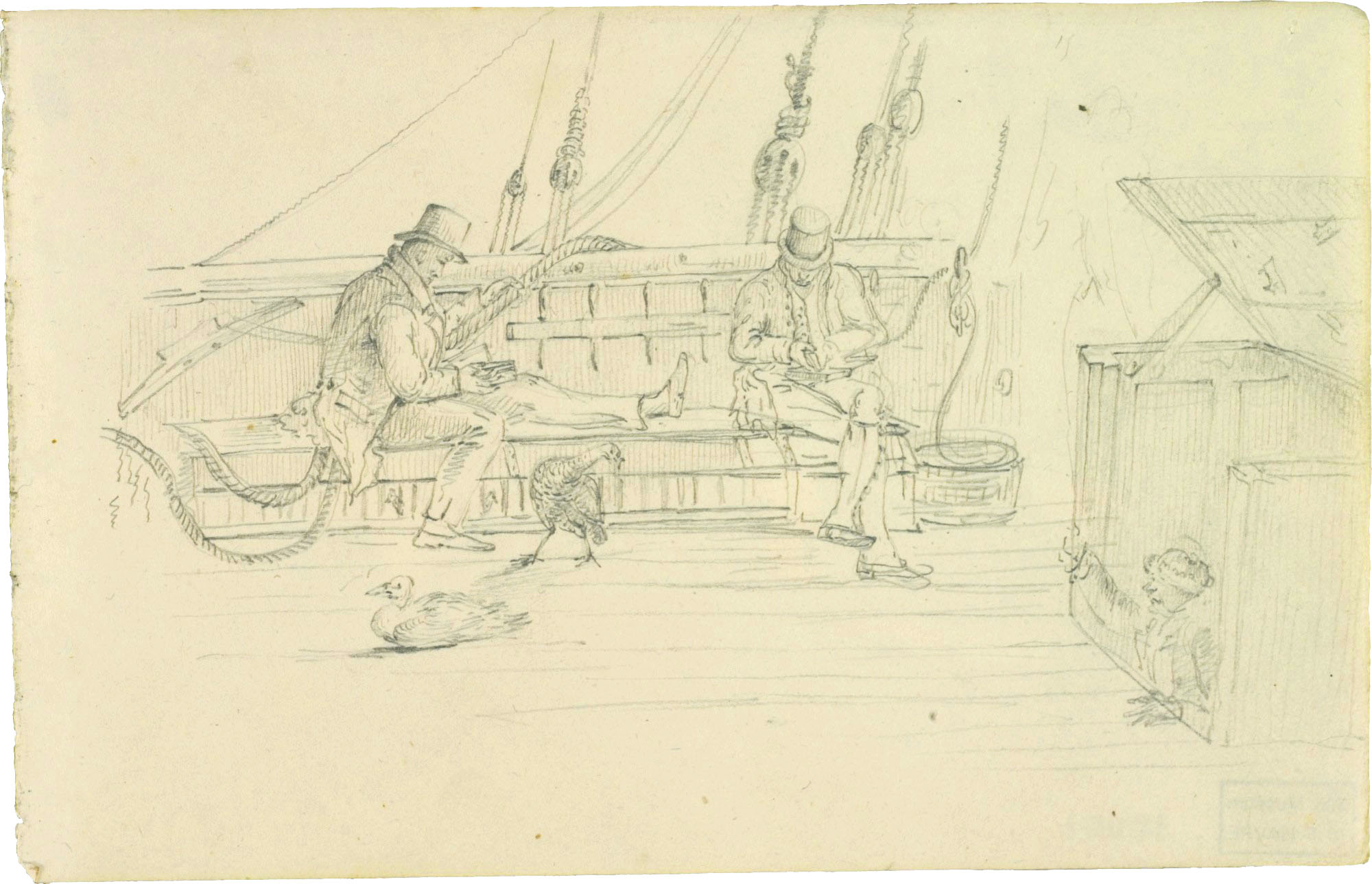

Travelers on the Louisia (Atlantic Ocean), by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1815) - Lesueur Collection 38 003, Natural History Museum of Le Havre.

|